Fodi Kyriakos explores how the COVID-19 pandemic could be the catalyst for change in radiology and encourages our community to grasp the opportunity to “seize the moment” and plan for recovery.

Fodi Kyriakos explores how the COVID-19 pandemic could be the catalyst for change in radiology and encourages our community to grasp the opportunity to “seize the moment” and plan for recovery.

At the beginning of 2020, if someone had told radiology leaders that all NHS outstanding reporting backlogs would be reduced to virtually zero by May, I’m sure they would have looked at you in disbelief and asked what sorcery had been involved, but this situation is exactly where we find ourselves today.

Normalcy Bias – Noun [edit]

normalcy bias (plural normalcy biases)

The phenomenon of disbelieving one’s situation when faced with grave and imminent danger and/or catastrophe. As in over focusing on the actual phenomenon instead of taking evasive action, a state of paralysis.

Historical challenges

In the past, it has often taken lots of effort to either invoke or accept change of any kind in radiology and for those managing services, there’s also been a certain amount of risk associated with putting your head above the parapet or being a trailblazer. It has been sometimes easier to follow the well-trodden path rather than to create a new one. Workloads and budgetary constraints have also been a disabler, restricting decision making to the ‘here and now’. This has resulted in failing, or in most cases, not being able to foresee or plan for events that have never happened before, such as an event like a pandemic crisis. Psychology refers to this state of being as normalcy bias. For those who are not familiar with the term, you will certainly be aware of its connotations and radiology now finds itself at this cross-roads.

Ever since the introduction of digital radiography and PACS, NHS radiology reporting backlogs have been a contentious issue among experts, and a recurring feature in the mainstream media! Often being highlighted (and with some justification) in relation to areas such as missed cancer diagnosis, where even the slightest of delays can have a significant bearing on the overall outcome.

Serious backlogs

The extent to which backlogs were a serious issue in the UK was further exacerbated by various Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections, which raised concerns regarding reporting backlogs that resulted in delayed or missed diagnosis of conditions that may have otherwise been picked up.

By the end of February 2020, the situation of backlogs was as much an issue as at any time before. Insufficient reporting capacity had led to a build-up of outstanding reports, which in turn meant that outsourcing was at its highest ever levels and growing pressures to meet new deadlines, such as the cancer pathway targets, were increasingly exposing the lack of options available to resolve the problem.

So, you would have been excused if you thought that a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic would simply exacerbate the reporting challenges facing radiology. However, this has not been the case. Instead, we have witnessed radiology’s own “clear the decks” exercise, where in fact the complete opposite situation has occurred, resulting in backlogs across the UK being virtually eliminated. Who would have thought that the worst crisis to hit the country (and the world) in 75 years would be a catalyst for NHS radiology departments to press the reset button?

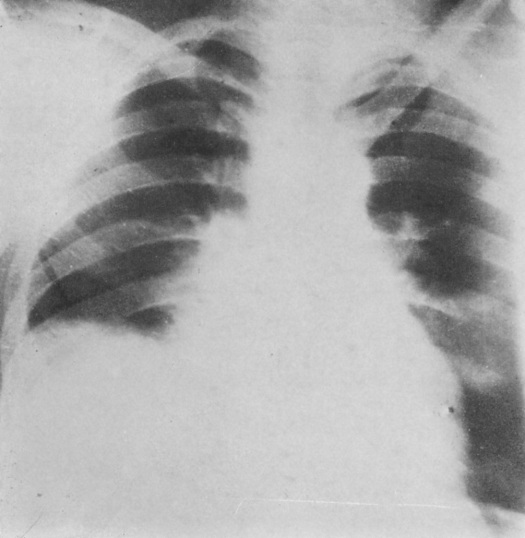

Of course, we recognise the superficial nature of this situation. During the pandemic, practically all routine referral activity came to a grinding halt, which allowed radiology to concentrate on COVID-19 and Emergency Department (ED) patients. Chest X-rays and CTs were identified as two of the key diagnostic tools for the virus, but the volumes were manageable. Accident and Emergency footfall was reduced to almost 50% of its usual figures, so reporters were practically able to deliver a ‘Hot-Reporting’ examination for every patient requiring imaging. Something which ED and Intensive care unit (ICU) consultants have grown quickly accustomed to.

During this time, radiology was also still required to work to critical staffing levels, so radiographers and radiologists were covering 24/7 rotas, but due to the lack of activity outside of portable X-ray scanning in ICU, many staff were not being utilised. So, while this enabled the catch up in radiology reporting to take place, what we witnessed was the ‘ying and yang’ of radiology. On the one hand, integral to the continuity of a patient’s pathway and critical to defining an outcome – AND on the other hand, completely dependent on throughput from referrers to maintain activity levels.

Seizing the moment!

So what happens next? Well, in a world where we can guarantee almost nothing, in this situation, we can guarantee that radiology will remain the centre point for the recovery phase of the pandemic, but with the added challenge of complying to ‘social distancing’ and ‘equipment cleaning’ guidelines, how do we manage the continuation of treating COVID-19 patients, while reintroducing ‘business as usual’ and ‘deferred’ patients whose treatment has been delayed?

The “Reset Button” has enabled something else to happen. For the first time, there is now some headspace to plan for the recovery phase and for the next phase at least, there is now funding available to support the recovery. So how do we avoid going back to where we were before the pandemic? How do we seize the moment?

Time to make the changes!

Albert Einstein once famously said: “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” This quote has never been more poignant in the present day and while the pressure to manage change will be at its highest, this is the right time to make these changes happen! With the benefit of ‘The Reset Button’, if we can learn from the past and apply new ways of working moving forward, we can avoid falling into the trap of the normalcy bias and witness the radiology reset button offering a new, efficient and more streamlined radiology department moving forward.

Everything you wanted to know about radiology but were afraid to ask…

On Wednesday 17 June, a live event organised by InHealth, in partnership with The British Institute of Radiology and the Society of Radiographers is taking place, titled: “The Radiology reset button has been pressed”. The aim is to tackle these challenges and support radiology managers as they enter the recovery phase. It will bring together senior figures from radiology and within healthcare to offer insights, opinions and advice on how we can approach this coming period and use what positives we have experienced during the pandemic to create service improvements throughout radiology.

There will be opportunities for radiology managers, clinical leads, radiographers and radiologists to put their questions to the speakers in the panel discussions after their presentations.

REGISTER FOR THE RADIOLOGY RESET BUTTON HAS BEEN PRESSED HERE

(The event is free for all)

About Fodi Kyriakos

Mr Fodi Kyriakos is a former director of RIG Healthcare and founder of RIG Reporting,

the UK’s first provider of external radiographer reporting services. In 2016 he joined The InHealth Group following its acquisition of RIG Reporting and is now the Head of Reporting across the Group. His service specialises in delivering plain film reporting solutions and is the only provider to offer both on-site and telereporting services.

Fodi has over 22 years experience in workforce and staffing solutions and 17 years working exclusive within Imaging and Oncology. He is a member of the Institute of Healthcare Managers and a regular contributor of professional development events across radiology.