Cheryl Cruwys, European Education Coordinator at DenseBreast-info.org/Europe, highlights the importance of understanding the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue. DenseBreast-info.org’s mission is to advance breast density education and address the gap in knowledge about dense breasts.

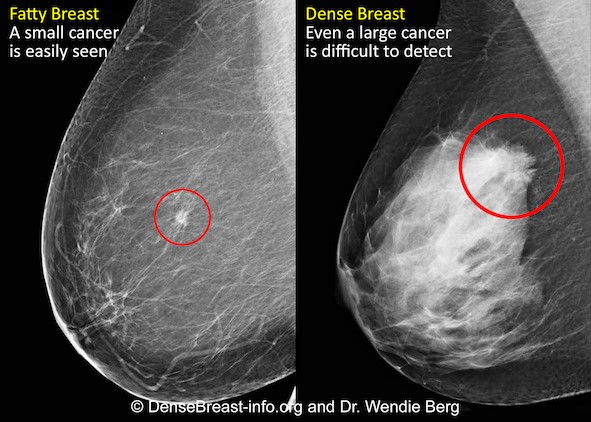

Mammography remains the standard of care in screening for breast cancer and has been proven to reduce the mortality rate [1]. However, in dense breasts, cancers can be hidden/obscured on mammography [2,3] (Fig.1) and may go undetected until they are larger and more likely to present with clinical symptoms [4]. Breast density has also been identified as the most prevalent risk factor for developing breast cancer [5].

Women with dense breasts are BOTH more likely to develop breast cancer and more likely to have that cancer missed on a mammogram [5]

What is Dense Breast Tissue?

Breasts are made of fat and glandular tissue, held together by fibrous tissue. The more glandular and fibrous tissue present, the “denser” the breast. Breast density has nothing to do with the way breasts look or feel. Whilst dense breasts are normal and common, dense breast tissue makes it more difficult for radiologists to detect cancer on a mammogram.

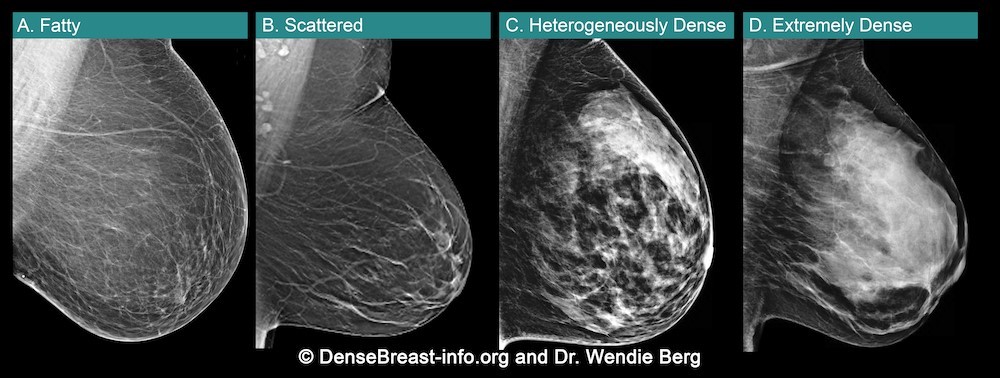

Breast density is determined through a mammogram and described as one of four categories (Fig. 2), (A) Fatty, (B) Scattered, (C) Heterogeneously Dense, (D) Extremely Dense. Breasts that are (C) heterogeneously dense, or (D) extremely dense are considered “dense breasts”. Fig. 2

Dense Breasts Facts

- 40% of women over age 40 have dense breasts.

- Dense breast tissue is an independent risk factor for the development of breast cancer; the denser the breast, the higher the risk.

- Mammograms will miss about 40% of cancers in women with extremely dense breasts.

- Women with extremely dense breasts face an increased risk of late diagnosis of breast cancer.

- In these women, screening tests, such as ultrasound or MRI, when added to mammography, substantially increase the detection of early-stage breast cancer.

Dense Breast Educational Resources

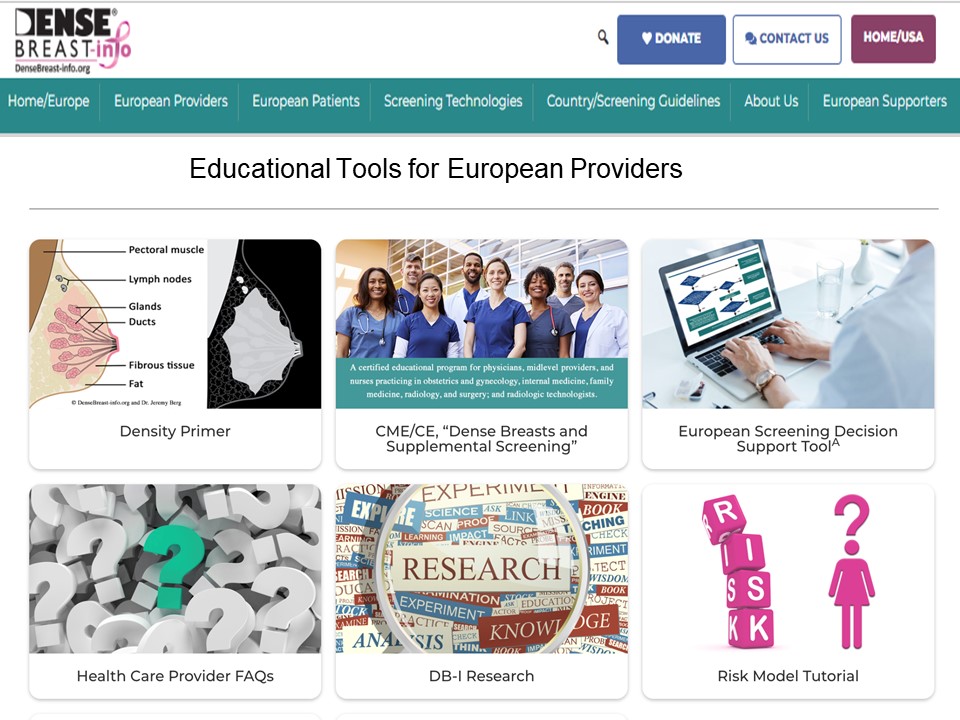

DenseBreast-info.org/Europe is the world’s leading website about dense breasts. This medically-sourced resource is the collaborative effort of world-renowned experts in breast imaging and medical reviewers. Fig 3.

The website features educational tools for both European Patients and Providers Fig. 4. (a and b)

CME Course – Learn Why Breast Density Matters!

The DenseBreast-info.org resource includes a free CME/CE course, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening suitable for primary care healthcare providers, including family medicine, internal medicine, and OB/GYN physicians and midlevel providers, as well as radiologists, and radiologic technologists (UEMS-EACCME® mutual recognition for AMA credits).

A growing number of medical organisations link to the DenseBreast-info.org website, including the EFRS (European Federation of Radiographer Societies) and the Society of Radiographers.

The website includes breast screening guidelines in Europe. A comparative analysis table summarises the guidelines in each country.

NHS Breast Screening Programme

Currently in the UK, population routine screening mammograms are offered to women aged 50–74, every 3 years. Though dense breasts affect the likelihood that a cancer will be masked and increases a woman’s risk for developing breast cancer, it is not part of UK data collection. A woman’s breast density is not assessed, not recorded in medical records, nor reported to her. For diagnostic purposes, this may differ. However, in many other European country screening programs, a woman’s breast density is assessed, recorded, and the woman’s personal breast density category is included in the mammography report.

News in Europe: the EUSOBI Recommendations

Population based breast screening guidelines vary across Europe. In the UK, asymptomatic women attending routine national breast screenings receive mammography alone. In some countries (e.g., Austria, Croatia, Hungary, France, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland) screening guidelines for women with dense breasts include that they be offered supplement ultrasound following a mammogram.

Following recent MRI screening trials there is cumulating evidence which confirms that women with dense breasts are underserved by screening with mammography alone [7,8]. In March 2022, new guidelines were issued in Breast cancer screening in women with extremely dense breasts by the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) [9] highlighting the growing evidence, particularly the results of a randomised, multicentre controlled study, the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) Trial. [7,8]

The European Society of Breast Imaging 2022 recommendations now step away from the one-size-fits all approach of mammography that is currently adopted by most European screening organizations and advocates for tailored screening programmes. There is compelling evidence that the new recommendations enable an important reduction in breast cancer mortality for these women.

Summary of the EUSOBI Recommendations

Below is EUSOBI’s summary graphic of the recommendations (Fig. 7) that highlight:

- Supplemental screening is recommended for women with extremely dense breasts.

- Supplemental screening should be done preferably with MRI …. where MRI is unavailable… ultrasound in combination with mammograph may be used as an alternative.

In addition to recommended additional screening in women with extremely dense breasts, note that EUSOBI recommends that “women should be appropriately informed about their individual breast density in order to help them make well-balanced choices.”

EUSOBI acknowledges that it may take time before the new recommendations are implemented in Europe and that the level of implementation is dependent on the resources that are available locally.

It is important to emphasize that the EUSOBI recommendations highlighted in this article are not yet guidelines in Europe. Of course, it is hoped that in Europe, national breast screening committees try to implement these recommendations as soon as possible to benefit women.

World Dense Breast Day Success!

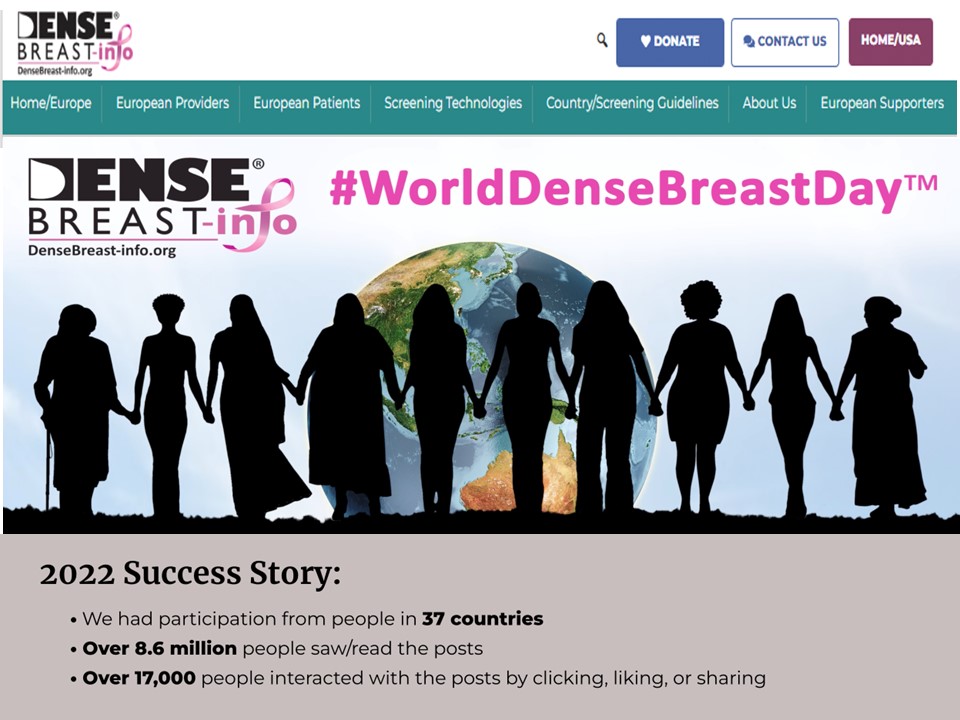

DenseBreast-info.org launched the first #WorldDenseBreastDay on 28 September 2022.

Nearly 100 posts with great images were created and ran for 24 hours across social media channels. Analytics detailed participation from people in 37 countries, over 8.6 million people saw/read the posts and over 17,000 people interacted with the posts.

The purpose of the day is to raise awareness about dense breasts and share medically-sourced educational resources available for women and health providers.

Please join us next year for #WorldDenseBreastDay which will take place on 27 September 2023!

Take Home Message:

- Breast density can both hide cancers on a mammogram and increases the risk of developing breast cancer.

- Women with dense breasts benefit from additional screening tests after their mammogram

- Breast density education and access to supplemental screening can mean the difference between early- or late-stage diagnosis

- Physicians should be educated and prepared to have patient conversations about breast density

- For more information about Dense Breasts visit: DenseBreast-info.org/Europe

——————————————————————————————————-

1, Tabar L, Vitak B, Chen T H et al. Swedish two-county trial: impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology 2011;260:658-63

2. Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM, Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE (2012) Screening US in patients with mammographically dense breasts: initial experience with Connecticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology 265:59–69

3. Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH (2002) Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology 225:165–175

4. RoubidouxMA, Bailey JE,Wray LA, HelvieMA(2004) Invasive cancers detected after breast cancer screening yielded a negative result: relationship of mammographic density to tumor prognostic factors. Radiology 230:42–48

5. McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I (2006) Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a metaanalysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:1159–1169

6. Vourtsis A, Berg W A. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol 2019;29:1762-77.

7. Bakker M F, de Lange S V, Pijnappel R M et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2091-102.

8. Stefanie G. A. Veenhuizen, Stéphanie V. de Lange, Marije F. Bakker, Ruud M. Pijnappel, Ritse M. Mann, Evelyn M. Monninkhof, Marleen J. Emaus, Petra K. de Koekkoek-Doll Published online: Mar 16 2021 https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021203633Radiology Vol. 299, No. 2 Supplemental Breast MRI for Women with Extremely Dense Breasts: Results of the Second Screening Round of the DENSE Trial

9. Mann, R.M., Athanasiou, A., Baltzer, P.A.T. et al. (2022) Breast cancer screening in women with extremely dense breasts recommendations of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) Eur Radiol 32, 4036–4045

Cheryl Cruwys is a British breast cancer patient, advocate, author and educator. While living in France (2016) she was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and credits the early detection of breast cancer to the French standard practice of performing supplemental screening on dense breast tissue. She is founder of Breast Density Matters UK, European Education Coordinator at DenseBreast-info.org/Europe, a member of the European Society of Radiology Patient Advisory Group and a Patient Rep on the ecancer.org Editorial Board.

Cheryl works at the European level with patient advocacy and medical societies, attends/presents at key scientific symposiums and works with international breast imaging experts to disseminate education on dense breasts. DenseBreast-info.org

Fodi Kyriakos explores how the COVID-19 pandemic could be the catalyst for change in radiology and encourages our community to grasp the opportunity to “seize the moment” and plan for recovery.

Fodi Kyriakos explores how the COVID-19 pandemic could be the catalyst for change in radiology and encourages our community to grasp the opportunity to “seize the moment” and plan for recovery.

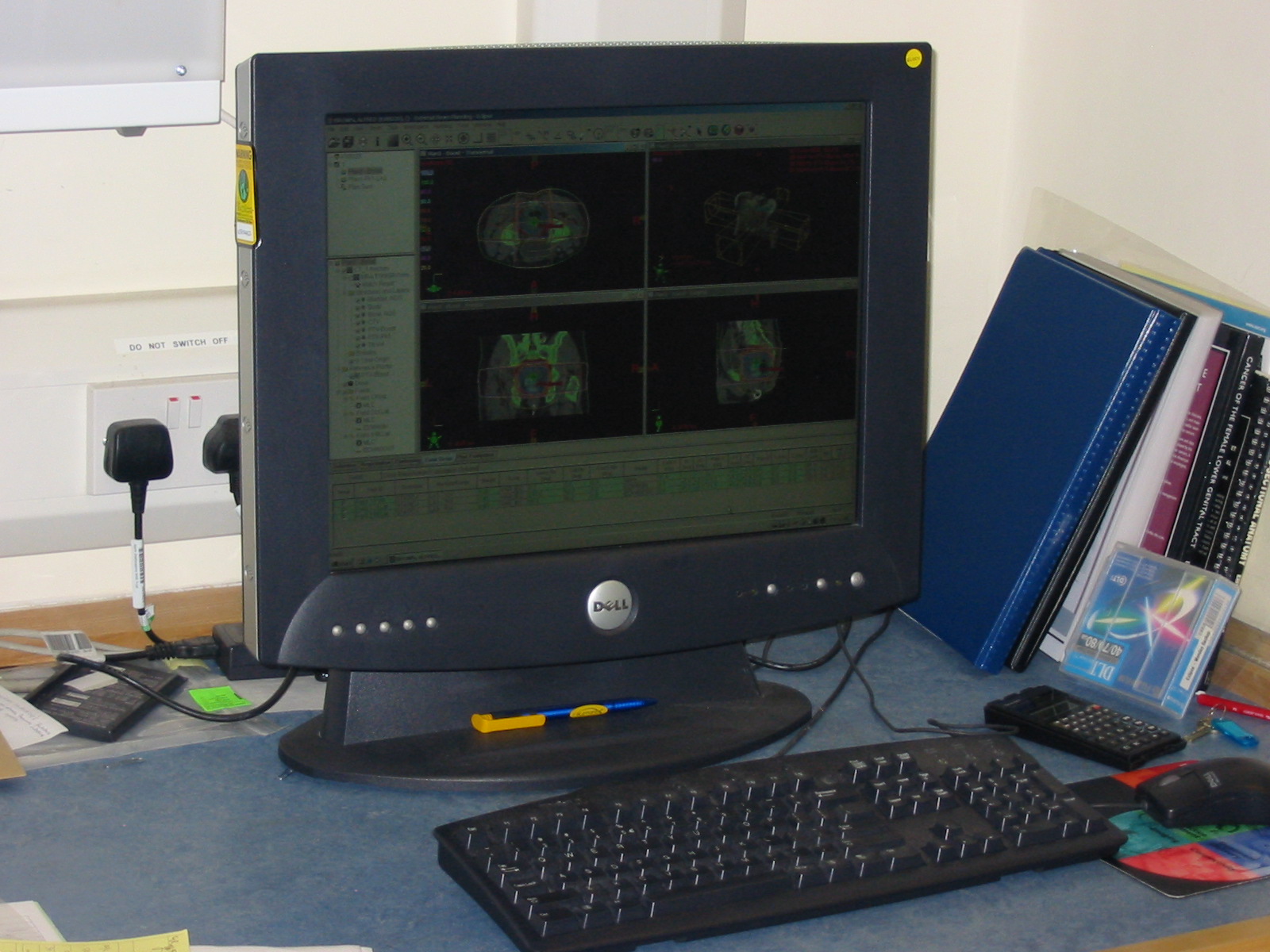

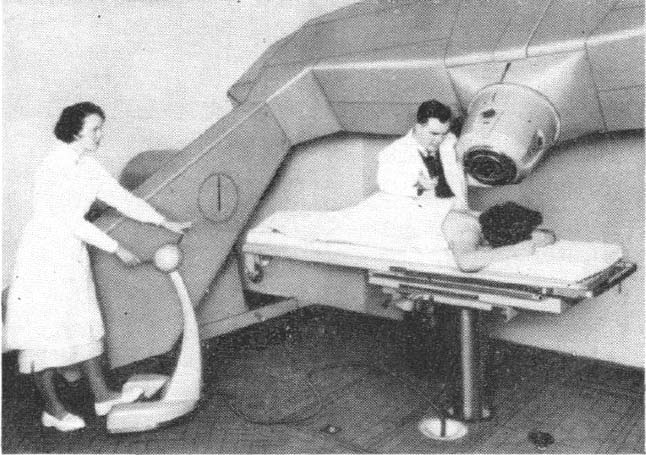

This was a time when, in this Cinderella of specialties, physics planning was achieved by the superposition of two dimensional radiation plots (isodoses) ,using tracing paper and pencils, to produce summated maps of the distribution. The crude patient outlines were derived from laborious isocentric distance measurements augmented by the essential “flexicurve”. The whole planning process was slow and labour intensive fraught with errors and ridiculed by colleagues in the perceived prestigious scientific and clinical disciplines. The principal platform for external beam radiotherapy delivery, the Linear Accelerator (LinAc), had also reached something of a plateau of development, albeit with improved reliability, but few fundamental changes. Caesium tubes were transported from the “radium safe”, locked in an underground vault, to the operating theatre in a lead-lined trolley, where they were only loaded into “central tubes” and “ovoids” after the examination under anaesthetic (which was performed with the patient in the knee-chest position); they were then manually placed into the patient, who went to be nursed on an open ward, albeit behind strategically placed lead barriers.

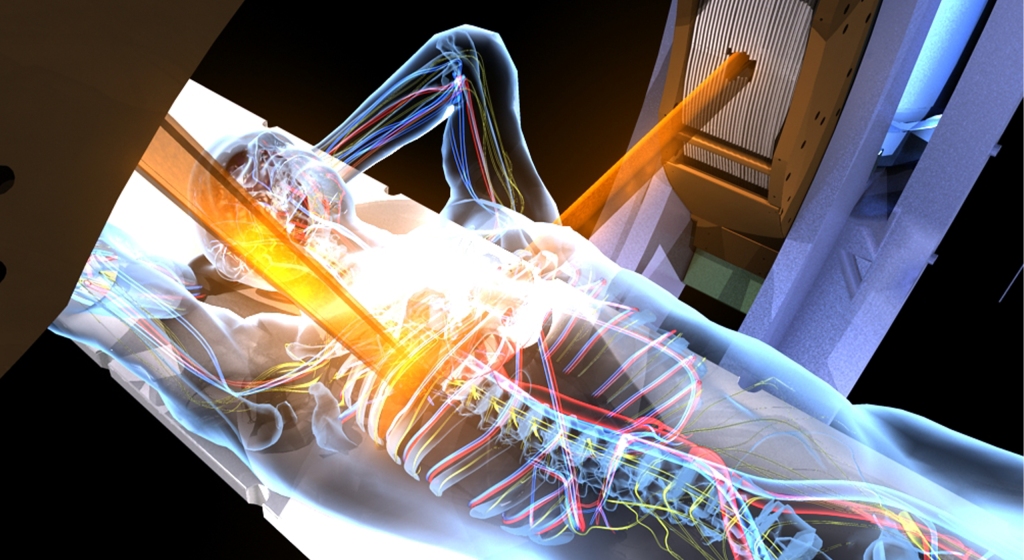

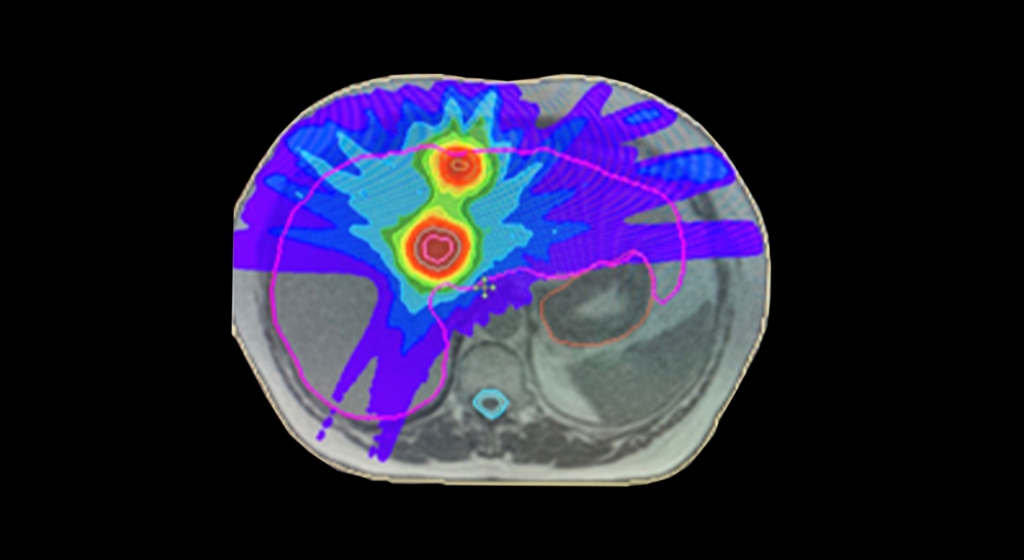

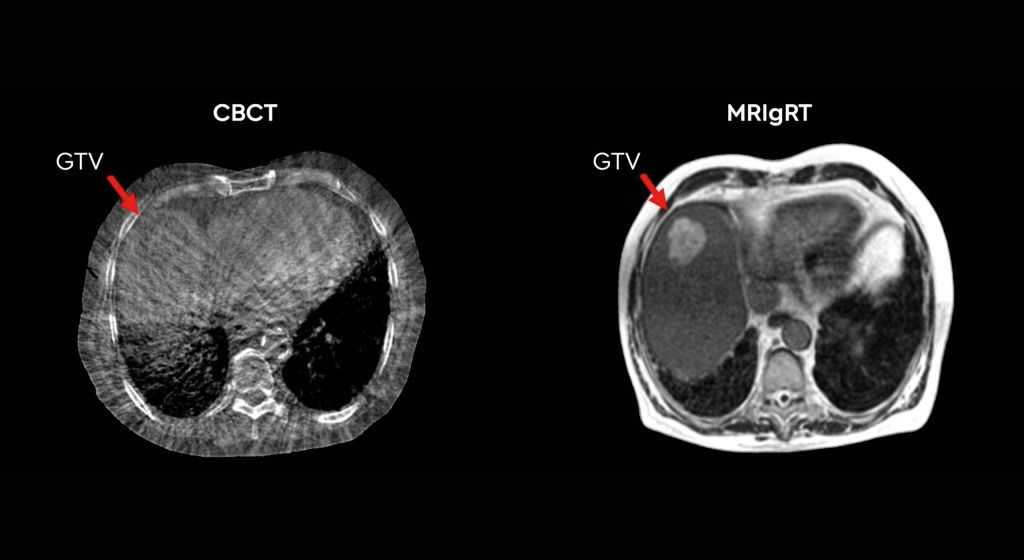

This was a time when, in this Cinderella of specialties, physics planning was achieved by the superposition of two dimensional radiation plots (isodoses) ,using tracing paper and pencils, to produce summated maps of the distribution. The crude patient outlines were derived from laborious isocentric distance measurements augmented by the essential “flexicurve”. The whole planning process was slow and labour intensive fraught with errors and ridiculed by colleagues in the perceived prestigious scientific and clinical disciplines. The principal platform for external beam radiotherapy delivery, the Linear Accelerator (LinAc), had also reached something of a plateau of development, albeit with improved reliability, but few fundamental changes. Caesium tubes were transported from the “radium safe”, locked in an underground vault, to the operating theatre in a lead-lined trolley, where they were only loaded into “central tubes” and “ovoids” after the examination under anaesthetic (which was performed with the patient in the knee-chest position); they were then manually placed into the patient, who went to be nursed on an open ward, albeit behind strategically placed lead barriers. In the latter half of the eighties these solutions began to crystallise. Computers were being introduced across the NHS and their impact was not lost in radiotherapy. Pads of tracing paper were replaced with the first generation of planning computers. The simple “Bentley-Milan” algorithms could account for patient outlines accurately and speedily and optimising different beam configurations became practical. Consideration of Organs at Risk, as defined by the various International Commission on Radiation Units (ICRU) publications, became increasingly relevant. Recognition of the importance of delineating the target volumes and protecting normal tissue required improved imaging and this was provided by the new generation of CT scanners. In the nineties these were shared facilities with diagnostic radiology departments. However, the improvements provided by this imaging, enabling accurate 3-dimensional mapping of the disease with adjacent normal tissues and organs at risk, dictated their inclusion into every radiotherapy department soon after the millennium. The added bonus of using the grey scale pixel information, or Hounsfield numbers, to calculate accurate radiation transport distributions soon followed when the mathematical and computer technology caught up with the task. The value of MR and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging was also recognised in the diagnosis, staging and planning of radiotherapy and the new century saw all of these new technologies embedded within the department.

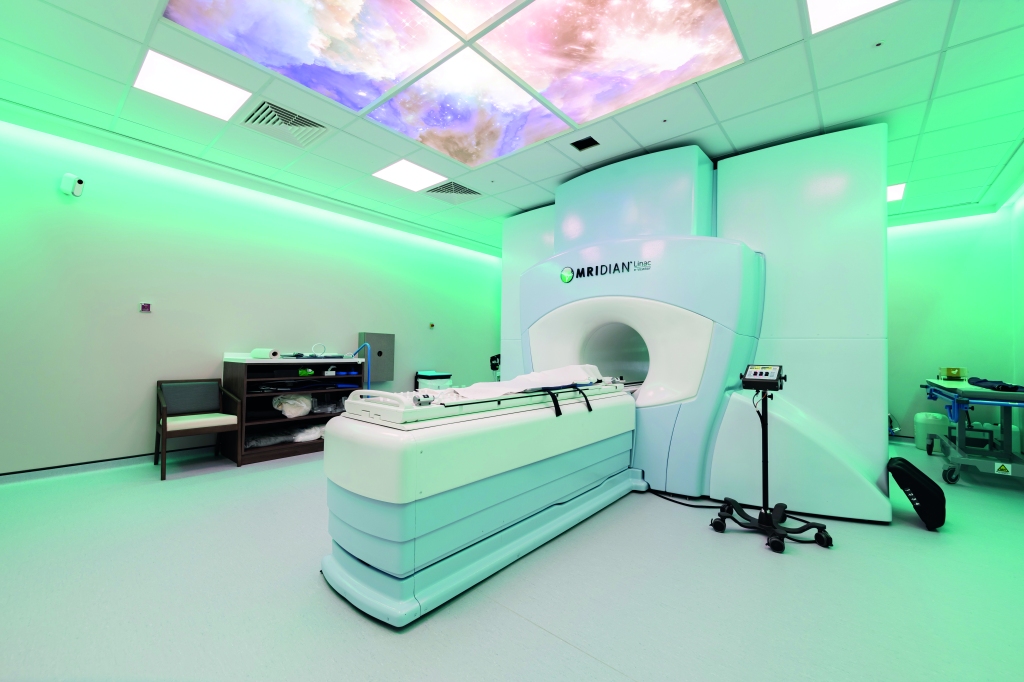

In the latter half of the eighties these solutions began to crystallise. Computers were being introduced across the NHS and their impact was not lost in radiotherapy. Pads of tracing paper were replaced with the first generation of planning computers. The simple “Bentley-Milan” algorithms could account for patient outlines accurately and speedily and optimising different beam configurations became practical. Consideration of Organs at Risk, as defined by the various International Commission on Radiation Units (ICRU) publications, became increasingly relevant. Recognition of the importance of delineating the target volumes and protecting normal tissue required improved imaging and this was provided by the new generation of CT scanners. In the nineties these were shared facilities with diagnostic radiology departments. However, the improvements provided by this imaging, enabling accurate 3-dimensional mapping of the disease with adjacent normal tissues and organs at risk, dictated their inclusion into every radiotherapy department soon after the millennium. The added bonus of using the grey scale pixel information, or Hounsfield numbers, to calculate accurate radiation transport distributions soon followed when the mathematical and computer technology caught up with the task. The value of MR and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging was also recognised in the diagnosis, staging and planning of radiotherapy and the new century saw all of these new technologies embedded within the department. LinAc technology also received added impetus. Computers were firstly coupled as a front end to conventional LinAcs as a safety interface to reduce the potential for “pilot error”. Their values were soon recognised by the manufacturers and were increasingly integrated into the machine, monitoring performance digitally and driving the new developments of Multi Leaf Collimators (MLC) and On Board Imaging (OBI).

LinAc technology also received added impetus. Computers were firstly coupled as a front end to conventional LinAcs as a safety interface to reduce the potential for “pilot error”. Their values were soon recognised by the manufacturers and were increasingly integrated into the machine, monitoring performance digitally and driving the new developments of Multi Leaf Collimators (MLC) and On Board Imaging (OBI). Dr David A L Morgan began training in Radiotherapy & Oncology as a Registrar in 1977, and in 1982 was appointed a Consultant in the specialty in Nottingham, continuing to work there until his retirement in 2011. He joined the BIR in 1980 and at times served as Chair of its Oncology Committee and a Member of Council. He was elected Fellow of the BIR in 2007. He is author or co-author of over 100 peer-reviewed papers on various aspects of Oncology and Radiobiology.

Dr David A L Morgan began training in Radiotherapy & Oncology as a Registrar in 1977, and in 1982 was appointed a Consultant in the specialty in Nottingham, continuing to work there until his retirement in 2011. He joined the BIR in 1980 and at times served as Chair of its Oncology Committee and a Member of Council. He was elected Fellow of the BIR in 2007. He is author or co-author of over 100 peer-reviewed papers on various aspects of Oncology and Radiobiology. Andy Moloney completed his degree in Physics at Nottingham University in 1980 before joining the Medical Physics department at the Queens Medical Centre in the same city. After one year’s basic training in evoked potentials and nuclear medicine, he moved to the General Hospital in Nottingham to pursue a career in Radiotherapy Physics and achieved qualification in 1985. Subsequently, Andy moved to the new radiotherapy department at the City Hospital, Nottingham, where he progressed up the career ladder until his promotion as the new head of Radiotherapy Physics at the North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary in Stoke-on-Trent. Over the next twenty years Andy has acted as Clinical Director for the oncology department and served on the Radiation Physics and Oncology Committees at the BIR and was appointed a Fellow in 2007. He has been the author and co-author of multiple peer reviewed articles over the years prior to his retirement in 2017.

Andy Moloney completed his degree in Physics at Nottingham University in 1980 before joining the Medical Physics department at the Queens Medical Centre in the same city. After one year’s basic training in evoked potentials and nuclear medicine, he moved to the General Hospital in Nottingham to pursue a career in Radiotherapy Physics and achieved qualification in 1985. Subsequently, Andy moved to the new radiotherapy department at the City Hospital, Nottingham, where he progressed up the career ladder until his promotion as the new head of Radiotherapy Physics at the North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary in Stoke-on-Trent. Over the next twenty years Andy has acted as Clinical Director for the oncology department and served on the Radiation Physics and Oncology Committees at the BIR and was appointed a Fellow in 2007. He has been the author and co-author of multiple peer reviewed articles over the years prior to his retirement in 2017.

Today’s NHS is nothing like the one I joined in 1966 and specialised scientist training is much more formalised and incalculably better. No one these days could be appointed in the manner that I had been but Dr B, like most other NHS professionals then and now, was motivated by good intentions and his thoughtfulness over fifty years ago put me on the path to a rich and fulfilling career in medical physics and radiobiology. I discovered later in life that Dr B had told one of his colleagues that he had helped me because he “wanted to give the lad a chance”. What he gave me was a chance that was truly exceptional and this lad has been immensely grateful ever since.

Today’s NHS is nothing like the one I joined in 1966 and specialised scientist training is much more formalised and incalculably better. No one these days could be appointed in the manner that I had been but Dr B, like most other NHS professionals then and now, was motivated by good intentions and his thoughtfulness over fifty years ago put me on the path to a rich and fulfilling career in medical physics and radiobiology. I discovered later in life that Dr B had told one of his colleagues that he had helped me because he “wanted to give the lad a chance”. What he gave me was a chance that was truly exceptional and this lad has been immensely grateful ever since.